Tourism is an important source of income for any city, region, or country. It was estimated that in 2013 tourism was “worth £106bn to England’s economy”(1). It should therefore come as no surprise that there is such a thing as a Tolkien tourist industry. For several decades Tolkien’s readers have been making private pilgrimages to Oxford; posing for photographs outside one of his residences; visiting the various colleges at which he studied, or where he later became a tutor and lecturer; paying their respects at his graveside, or even dropping in to ‘The Eagle and Child,’ one of his favourite pubs, for a drink. The tourist industry is now galvanising its resources and offering dedicated Tolkien Tours. In April this year Birmingham produced a new Tolkien Trail leaflet, which recommends visits to Sarehole Mill, Moseley Bog, the houses where Tolkien once lived, and the places he worshipped. This is an invaluable resource for those wishing to visit all the genuine sites associated with Tolkien in the area in which he grew up. However, a more pernicious aspect of tourism is also beginning to rear its head; locations which have only a tangential Tolkien connection, or in extreme cases with absolutely no link to the author are attempting to jump on the tourist bandwagon.

For instance, the beautiful and ancient Puzzlewood in the Forest of Dean has recently started to market itself by claiming “JRR Tolkien is reputed to have taken his inspiration for the fabled forests of Middle-earth from Puzzlewood” (2). However, this statement does not hold up to scrutiny. Nowhere in any of the professor’s published writings or letters does he actually mention visiting Puzzlewood, and on further investigation there is no evidence he even visited the Forest of Dean of which Puzzlewood is a part. There is not even an entry for Gloucestershire in the whole of Hammond & Scull’s exhaustive Reader’s Companion. Puzzlewood is not alone, similarly Kinver Edge in Staffordshire has some remarkable picturesque rock houses, which have been promoted by some, but not the National Trust, as the original of hobbit holes. However, there is no proof that Tolkien ever saw them before he wrote The Hobbit, and he never even refers to them after it was published. A more complicated problem arises when places known to have had a late connection to Tolkien are being advertised as being an inspiration for his writings.

Visit Lancashire, the Lancashire tourist board, has produced a classy authoritative-seeming Tolkien trail leaflet which makes much of Stonyhurst College’s genuine Tolkien associations. The leaflet hints that the river Shirebourn and that Shire Lane in Hurst Green may be connected to The Shire in Tolkien’s books. They are bolder in respect of the ferry at Hacking Hall and suggest this “may have provided the inspiration for Buckleberry Ferry in the book” (3). Christopher Tolkien’s work on his father’s original drafts in The Return of the Shadow show that the ‘Second Phase’ of The Lord of the Rings in which Buckleberry Ferry is first mentioned by name was in existence by October 1938 (4). John Tolkien did not arrive at Stonyhurst to study for the priesthood until several months after May 1940. The professor would have had no reason to visit Stonyhurst before his son’s arrival there, and his first documented visit to Stonyhurst appears to have been on 25th March 1946 (5). Therefore the alleged inspiration of Buckleberry Ferry from the one at Hacking Hall would appear to be absolutely non-existent. Yes, Tolkien visited Stonyhurst College several times after 1946, but by that time his writing had reached the Minas Tirith chapters, so to claim his visits inspired his depiction of the Shire appear rather disingenuous.

Stonyhust College is not a singular example, new claims have been proliferating more swiftly than Farmer Maggot’s mushrooms. These include the Burren in Ireland, Ethiopia in Africa and even an area of America. It is in this period of ever increasing claim-staking for inspiration that it is appropriate to draw attention to a neglected, but genuine Tolkien inspiration: Roos and the surrounding East Yorkshire countryside.

It must have been in 1981 on publication of the Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien that I became aware that a small village called Roos was mentioned three times. Could this actually be the same tiny place I was taken as a child when my father was working near the church? On further investigation it soon became clear that Tolkien’s Roos was identical to the one I knew in East Yorkshire. I can still recall how surprised I was to learn that Tolkien was inspired to write about the Elven princess Lúthien Tinúviel by watching his young wife dance and sing for him in a wood near the seemingly-insignificant backwater of Roos. Shortly afterwards I tracked down Humphrey Carpenter’s J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. It was evident from the biography that Tolkien was stationed for a brief period in the Roos area, and also convalesced for a time at Brooklands Officers’ Hospital in Hull, but the account is not very detailed, and allied with the breezy tone of the book, the war period, despite the inherent and obvious dangers doesn’t appear as especially significant in Tolkien’s long life and writing career.

The impact of Tolkien’s stay in East Yorkshire and his war service didn’t really coalesce for me until I first read John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War. It’s clear from the title alone that this work focuses on Tolkien’s time in the First World War, and by extension in the Holderness area of Yorkshire, far more than Carpenter’s did. One also gets the impression that Garth actually visited the East Yorkshire locations and understood how these unique landscapes affected and inspired a writer in a way Carpenter’s rather “Oxford-centric” approach never manages. Indeed, although Garth is a professional journalist his prose takes on an almost poetic quality at times, especially when he is describing the eerie qualities of the topography and the fragility of the Holderness peninsula. Garth quietly modifies some of Carpenter’s incorrect dating of events, and provides more detail to the bones of the original skeletal biographical account. For instance, the dating of the inspirational dance at Roos is brought forward from 1918 to spring 1917; Tolkien’s time at Thirtle Bridge, Easington and Hornsea is fleshed out, and Brooklands is identified as being on Cottingham Road in Hull. Although I know many tiny nooks and crannies in Holderness, I had never even heard of Thirtle Bridge. This wasn’t surprising as Thirtle Bridge was a temporary army camp, only constructed for purposes of war, and not likely to leave a large architectural legacy. Garth highlights just what Tolkien was working on at his time in East Yorkshire, and includes several very acute analyses of specific poems and his emerging mythology, explaining just how and why they were affected and influenced.

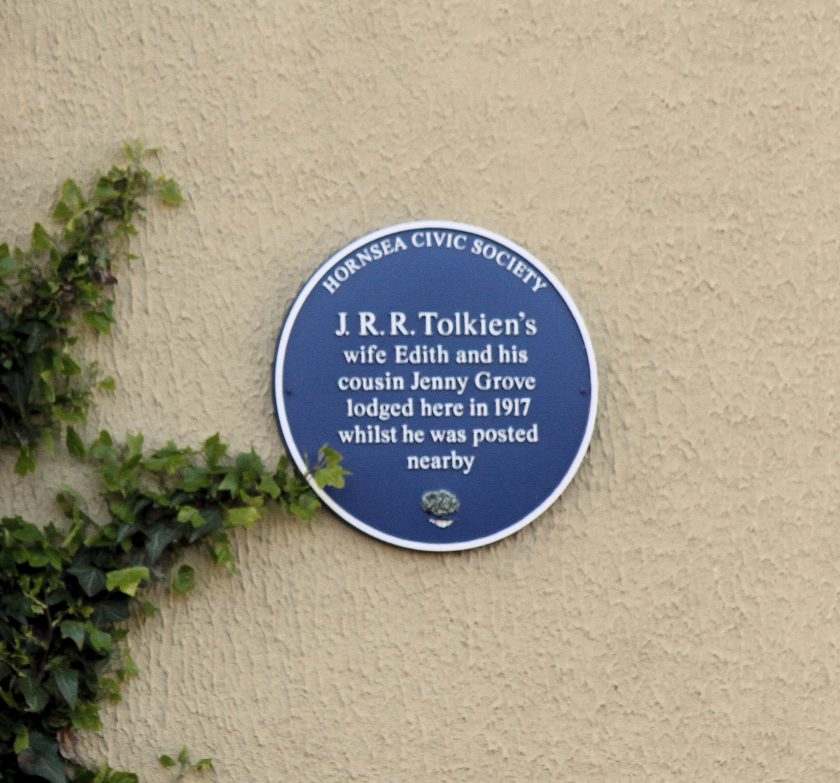

Finally, in 2012 a slim local volume was published which filled in several of the remaining blank spaces: Tolkien in East Yorkshire, 1917-18 by Phil Mathison. Unlike Carpenter’s breezy style, and Garth’s poetic journalistic approach, Phil Mathison’s meticulous workmanlike research sifted every available scrap of postcard, envelope, and war office medical board report in order to tease out as far as is possible an exact chronology and itinerary of Tolkien’s time in East Yorkshire. Therefore we learn of the exact addresses at which Edith and Jennie Grove lodged in Hornsea and Withernsea and for how long. Mathison even manages to locate some structures on the Thirtle Bridge site, and demonstrates that a couple of them have managed to survive into the 21st-century.

Mathison also pinpoints the precise modern-day location of Brooklands Officers’ Hospital, which unexpectedly is directly opposite the main entrance to Hull University. Mathison also reveals that Tolkien was treated at a second hospital at the Godwin Battery right on the edge of the thundering North Sea. This was the most surprising revelation of all for me, because for the last decade I’ve been leading my students past the exact spot on the way to watch some of Britain’s most threatened breeding sea birds.

It is now possible after Mathison’s research to follow in Tolkien’s footsteps in East Yorkshire, although wartime restrictions on information mean that some details still remain a little vague. We know that Tolkien was expected locally any time after 27th November 1916, but he didn’t actually arrive in East Yorkshire until 19th April 1917. Shortly afterwards Edith lodged at 1 Bank Terrace, Hornsea, while she thought Tolkien was going to be based at the nearby Hornsea musketry camp. However, when it became clear he was more likely to be stationed at the more distant Thirtle Bridge Camp she left Hornsea. There is no extant correspondence for the six weeks after Edith left Bank Terrace, so either letters have been lost, or there was no need for letters. It is possible that the young married couple may have been able to stay together for those six weeks. At the end of this time Edith took lodgings in Withernsea, which was only 3 miles from Tolkien at Thirtle Bridge. In May 1917 Edith danced near Roos, and the inspiration for Lúthien and Beren was sparked. On the 13th of August Tolkien was admitted to Brooklands officers’ Hospital for the first time. In total he spent more than twenty weeks of his eighteen months in the region in those congenial surroundings. It was at Brooklands that he was able to devote the longest concentrated time on his emerging mythology than at any earlier period. In that time he wrote the first versions of ‘The Tale of Tinúviel’ and ‘The Tale of Turambar.’ These are arguably the two most important and central narratives which make up The Silmarillion, and they were to take hold of Tolkien’s imaginative writing for decades to come. While Tolkien was hospitalised he was under the auspices of local land-owner Margaret Strickland-Constable. She was a keen linguist herself, apparently proficient in German, French, Swedish, Norwegian and Danish, and one wonders if she and the putative author discussed this common connection? It is known that Tolkien consolidated his knowledge of Italian and Spanish, and even began to study Russian while he was hospitalised. Of course Tolkien’s invented languages played a crucial part in his developing stories and he was also able to devote a considerable time expanding his lexicon and grammar of Qenya and Goldogrin, thus providing a substantial linguistic groundwork for his imaginative world.

After Mathison’s research there should not be much more new material to unearth regarding Tolkien’s time in East Yorkshire, but we can always remain hopeful. Some intriguing loose ends do still remain. For instance, when Tolkien was in the Humber Garrison he travelled to Dunstable to sit a signalling course exam in the second half of July 1917. Were Tolkien’s duties as a signalling officer connected in any way with the largest surviving remnant of the Great War in that part of Holderness? This is something which remained unmentioned by both Garth and Mathison. In 1916, according to local historian Jan Crowther, an Acoustic Sound Mirror was erected at Kilnsea to listen out for approaching Zeppelins and other aircraft. The sound was focussed by the concave dish to the “collector’s head” mounted on the metal pipe still visible in modern photographs, on which was a rudimentary microphone. Wires from this led down to a trench in which an operator with headphones would listen for approaching aircraft, and would provide an early warning. We will probably never know if Tolkien was one of those “listeners”, but even if not, when he was in Kilnsea he could not have failed to see this monumental concrete structure. Incidentally, this 16-feet high piece of concrete is still the only listed building in Kilnsea! (6). Tolkien spent months in the Easington and Kilnsea areas in winter, and as someone who came from the land-locked West Midlands, he must have seen at first-hand the truly destructive nature of the sea, possibly for the first time.

Obviously Oxford, and the areas around Birmingham are pre-eminently important in understanding Tolkien’s life and work, but East Yorkshire, although much more briefly connected to Tolkien, still played a crucial part in his life and as an inspiration for the foundation of his emerging mythology. Philip Larkin famously liked Hull, because it was out on the edge of things. However, Hull’s isolation doesn’t always work in its favour. Hull and Holderness are often sidelined from the mainstream because of their particular geological location, but currently they also seem to getting overwhelmed by the less authoritative claims of other localities. Tolkien unequivocally states that “the kernel of the mythology, the matter of Lúthien Tinúviel and Beren, arose from a small woodland glade filled with ‘hemlocks’ (or other while umbellifers) near Roos on the Holderness peninsula” (7). An explicit quote by Tolkien confirming his inspiration cannot be claimed by Puzzlewood, Kinver Edge, The Burren, Ethiopia or Pawneeland. Scholars who are interested in the true inspiration for Tolkien’s imaginative fiction will probably always remember the importance of the names of Roos and East Yorkshire. The question arises how will those with a more casual interest in the author be made aware of Tolkien’s connection with such a hidden area?

Hull’s tenure as City of Culture occurs in 2017, which coincides with the centenary of Tolkien’s residence in the area, and more significantly with the centenary of the genesis of the Beren and Lúthien story. Hopefully, an enterprising Tolkien aficionado will ensure that an event will be organised to celebrate and commemorate this momentous literary occasion, and simultaneously cement Tolkien’s links to the area in the minds of a wider community.

A very different version of this blog bringing out my personal connections with East Yorkshire and Tolkien may be read here: http://www.eybirdwatching.blogspot.co.uk/2014/08/tolkiens-ghostly-presence.html

Acknowledgements

This blogpost would not have been possible without the diligent research initially by John Garth and then by local author Phil Mathison.

All photographs (c) 2014 Michael Flowers, unless otherwise stated.

Footnotes

- Quoted: http://www.thetolkienist.com/2014/03/30/visit-england-visit-middle-earth-and-holiday-like-a-hobbit/

- Quote from Puzzlewood’s own website: http://www.puzzlewood.net/

- Leaflet: In the Footsteps of J.R.R. Tolkien.

- C. Tolkien, The Return of the Shadow, HarperCollins, London: 2003, pp.286-91. W. Hammond & C. Scull, The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion & Guide, HarperCollins, London: 2006, p. 221.

- W. Hammond & C. Scull, Ibid., p. 301.

- Jan Crowther, The People Along the Sand: The Spurn Peninsula & Kilnsea, Phillimore, Andover, 2010.

- H. Carpenter assisted by C. Tolkien, Selected Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, George Allen & Unwin, London: 1981, p. 221.