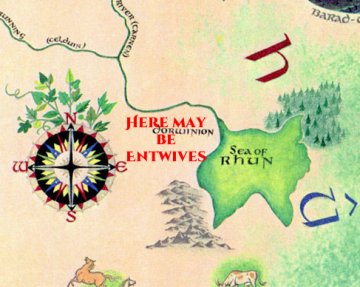

It may not be long now ere you hear that the Entwives have at long last been found. If you are a member of the Tolkien Society Facebook group then you may already know to what I refer. A quora user named Pip Willis published a partial image of a map he says his father drew and shared with J.R.R. Tolkien in 1971. Willis says that Tolkien wrote on the map, “Here may be Entwives”, which you can see in the picture he shared. And now the debates will begin. Is the map authentic? Is the writing Tolkien’s? Does it mean anything significant?

There is a long-running fascination with Entwives among Tolkien fans. Maybe not every reader cares what happened to them but Treebeard’s story is somewhat moving and it plays a significant role in his relationship with Merry and Pippin. There is a bit of character development there. But the Entwives themselves play no significant role in the story; nor do they appear in any of the abbreviated histories that Tolkien wrote.

One of the cool things about Tolkien’s Middle-earth is that you cannot neatly pin down every detail. It makes the story more interesting when it leaves you wondering what happened to so-and-so, or why such-and-such place is named as it is. A good walking tour of Middle-earth should enchant the tourists with a little mystery. “Sir! Sir! Why do they call this place Emyn Arnen?” “I don’t know, son, but it’s a lovely name, is it not?” I don’t need to know why it’s called Emyn Arnen. Not today.

Eventually, as this piece of datum is absorbed into the Internet of Fandom the rumor that Tolkien settled the issue will be born. It’s not enough that we only have an anecdote accompanied by a picture in which one can read “Here may be Entwives”. There will be no ambiguity for some, just as there is no ambiguity for those who believe that Tolkien’s elves have pointed ears (a fact he failed to mention in any story) or that Frodo held the One Ring up to his lips to speak through it to Gollum on the slopes of Mount Doom (in Gandalf’s voice, some say). The meaning of “Tolkien’s words” is always clear to those who have set their minds a certain way.

And I am one of the few who insists on spoiling the magic by asking why God needs a starship (or, rather, if Tolkien really meant it that way). He was annotating someone else’s uncommissioned map. It looks like a marvelous work of art, from what I can see of it. I am sure it is quite beautiful and I would love to have a print of it hanging on my wall. But Tolkien had a way of absorbing so many fan questions into his responses, suggesting that whatever you want to believe is not quite so unbelievable without precisely endorsing whatever your question suggests.

Bombadil needs no explaining, according to the author, but he offers some explanation anyway. Oh, he was just an adventure that Frodo needed along the way to Bree. Better yet, he was a pacifist and a neutral voice in the great debate. That was important to the story. But these kinds of responses are obfuscations, or at the very least obstructions. Tolkien used Bombadil in other ways, such as foreshadowing many things to come. But was the foreshadowing necessary to tell the story? And was it so much foreshadowing as providing a consistency to Middle-earth, which seems to be overflowing with walking trees, dark ghostly shapes, menacing dark things, and Gandalfian visions. Tolkien never provided a fully adequate, definitive explanation of who and what Bombadil is or why he is in the story.

Bombadil is not the “vanishing spirit of the Oxford countryside”, not when Frodo meets him, because there is no Oxford countryside when Frodo meets him. The application is external to the story. That is what Bombadil means but that is not Bombadil’s function in the story. Or maybe Bombadil was just a doll one of Tolkien’s children liked and Dad decided to include the doll in the story. It could be as simple as all that. We have heard as much.

If the words are indefinite (and Tolkien’s often are) then why are we so quick to proclaim definitive explanations for them? The absence of denial is the propagandist’s best argument in these matters. And so here we have a purported statement from Tolkien that coyly suggests maybe the Entwives survived the War of the Last Alliance and that they may have been on the map all along. Never mind the fact the Ents supposedly searched high and low for them. How did they miss such a logical place? Why didn’t Gondor’s kings run into these tree ladies when they were fighting enemy hordes throughout that region?

The drive to explain everything in the stories is potent magic. It has led us into the most awkward and twisted of logical arguments at least 10,000 times. 100,000 more such excursions surely lie before us. But before you raise that etymological essay as proof of the alignment of the sun and moon on Thursdays and Sundays, before you quote letter and paragraph, before you whip out that early map of Arda you need to answer one simple question: is it canon?

Canon is the soft underbelly of every interpretation, every scholarly paper, every thoughtful essay. There is no canon, and there are a thousand canons. Every idea put forward, either in jest or speculation, becomes canon for some. Only recently someone sent me a message, taking me to task for not declaring definitively that Gandalf ordered the Fellowship to ride the Eagles to Mordor. And that’s not the first time I have been told as much.

And so now this map, this simple fan-made map, opens anew a discussion that we have had before in different contexts. Where does one put all the little pieces of the puzzle that Tolkien let slip ex post liber? Take the matter of Orc women. There is plenty of evidence in the stories supporting the idea that Orcs must have been divided into two sexes, but you never hear about Orc women in the stories. This question is so vexing and obvious (despite the references to “breeding” programs) that at least one fan put it to Tolkien in a letter. And he saw fit to write back to dear Mrs. Munby and say:

‘There must have been orc-women. But in stories that seldom if ever see the Orcs except as soldiers of armies in the service of the evil lords we naturally would not learn much about their lives. Not much was known’

Well, that should clear it all up, should it not? Except … dare I ask it … did he say, “there must have been orc-women”? Did the man not KNOW? This is the Author of which we speak. Why couldn’t he just come out and say it: “Yes, Mrs. Munby, there were orc-women. I just didn’t have a reason to include them in the stories.” Now we have more of this ambiguity and here we thought we had settled the orc-woman question once and for all but because Tolkien was hesitant an argument, even a credible argument I daresay (for someone can surely find a passage suggesting orcs were made from stone or spawned), can be made that Orcs were not divided into two sexes.

Tolkien was a rather confusing fellow. His uncertainty permeates his fiction. He ambiguates rather than disambiguates because that makes the story more interesting. I can almost see a glint in his eye as he writes on the map, “Here may be Entwives”. Here is the kernel of a story and it need not be a truthful story. For could there not be legends that come down out of the shadows? That would be a great example of detail, a layer placed atop another layer. He sometimes wrote about the legendary matters of Middle-earth, retelling the stories that might or might not have been true.

Tolkien specialized in a sort of quantum fiction, where the details are both true and not true until the reader makes the decision. In such a world how do you choose what is canon, even if the author publishes everything he writes and gives it the stamp of authority? You’ll never settle all the questions. Maybe that is indeed what the old fellow had in mind after all. It would be a clever innovation and hard to replicate, especially given the reaction to Tolkien’s story-telling that has dominated modern fantasy fiction for the past 20 years. It’s hard to find an imaginary world where the author doesn’t try to explain everything in some way.

Those nice, neat packages of natural laws and boundaries and rules may only serve to diminish the story rather than enhance it because once the author has explained everything in every definitive way possible there is really no reason for the readers to continue thinking about the story.